газета Ставропольская правдаСтаця порусский |

Newspaper: The Stavropol TruthThe original article in Russian |

|||

| ПЯТНИЦА, 27 февраля, 2004 г — Николай БЛИЗНЮК | Friday, February, 27, 2004 — by Nikolay Blizniuk | |||

«Хлеб» радости, «хлеб» печали |

"Bread" of joy, "bread" of griefor: Meal of Joy, Meal of Grief |

|||

| Снаружи

– добротный сельский дом

из белого кирпича. Внутри —

просторная светлая комната. С потолка на

проводе свисает лампочка без абажура. На свежевыбеленных стенах лишь

шесть белых льняных полотенец с неброской вышивкой и больше никаких

украшений. Из мебели —

сколоченные из досок скамьи и стол. В углу три

белых полотенца (по аналогии со Святой Троицей) скрывают главную

ценность — огромную тяжеленную дореволюционную

Библию в переплете из

толстой коричневой кожи. |

Outside

it's a sound rural house

made of white brick. Inside it's a spaciously lit room. From the

ceiling a bulb on a

wire hangs down without

a lamp shade. On freshly whitewashed walls there are only six white

linen

towels without fancy embroidery, and there are no more decorations. For

furniture there are benches hammered together

from

boards and a table. In a corner, three white towels (by analogy to the

Sacred Trinity) hide the main treasure — a huge, old, heavy,

pre-revolutionary Bible bound in thick brown leather. |

|||

| Итак, мы с вами в церкви

христиан — молокан села Орбельяновка Минераловодского района. |

So here we are in a church of

Christians, in the Molokan village of Orbel'ianovka [Orbel'yanovka],

Mineral

Waters region. |

|||

|

||||

| «Шли

горами, шли лесами И зубчатым колесом. В тюрьмах, замках отдыхали И ко Господу взывали…». |

"We

walked through the mountains, we walked through the woods And through a cogwheel. We rested in prisons and in forts And appealed to the Lord …". |

|||

| Чувствую: мурашки по коже пошли.

И дело не в словах, не в берущей за душу мелодии. А в их глазах: они

вдруг стали бездонно глубокими.

Словно пронзили века и с болью и

состраданием следят, как их измученные, истерзанные, но непоколебимые

духом предки шагают в неведомую даль… |

I felt goosebumps [ants] on my skin. And it is not because of words, not because of a melody touching the soul, but because their eyes suddenly became profoundly bottomless. It was as if they [eyes] were pierced by the centuries, and they were watching, with pain and compassion, how their exhausted, tormented, but unbreakable, spirited ancestors marched to an unknown destination … | |||

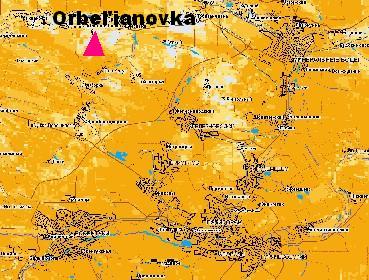

Orbel'ianovka is east of Mineralnye Vody in Stavropol' province. Минеральные Воды (Mineral Waters) is a regional center. Marked on the map below, there are 3 Molokan congregations in Piatigorsk, 2 in Inozemtsevo, plus 5 more in the "MinVod" region. |

||||

| Религиозные бунты сотрясали

Россию начиная с середины XIV века. Но особенно массово они проявились

в XVII веке. Формально «раскол» стал ответом на введение

патриархом Никоном греческой обрядности в ущерб строгому следованию

обычаям русской старины. Но на самом деле корни уходили гораздо глубже

—

в психологические и идеологические начала народного сознания. В том

же русле зарождались и на какое-то время приобретали множество

сторонников религиозно — реформационные движения. Это и христоверы

(«хлысты»), и скопцы, и субботники, и духоборы. И,

разумеется, молокане. |

Religious revolts shook Russia

since the middle of the 1300s. But they became especially massive in

the 1600s. In response to

an introduction by patriarch Nikon

of the Greek tradition, instead of strictly following the Russian

customs of olden times, a "split [raskol]" occurred.

But

the actual roots were much more deep into the psychological and

ideological beginnings of the national consciousness. In the same

course they arose, and for some time, got many supporters of the

religious Reformation movements. These are both the Khristovery

("Whips")

and Skoptsy; both

the Subbotniki and Dukhobors; and

certainly the Molokans. [Also see Wikipedia.org Category:

Eastern Orthodox minor churches and movements] |

|||

| Основатель молоканства —

бродячий деревенский портной из тамбовской губернии С. Уклеин —

провозгласил идеалом первоначальное христианство, не искаженное

соборами. Его последователи отказались поклоняться иконам и всему, что

создано руками человека, считая это идолопоклонством. Поклоняться можно

только Богу Живому. Отказались от креста, поскольку, мол, неуместно

славить орудие убийства. Отсчёт праздников стали вести только по

лунному календарю. И, наконец, полностью отвергли церковную иерархию,

институт священнослужителей, каких бы то ни было святых и предания,

признавая Словом Божьим только Библию. В ответ последовали жестокие

репрессии властей и официальной церкви. Одной из мер борьбы с

религиозными отступниками стала высылка за Кавказкий хребет.

Рассчитывали, что «духовные христиане» там либо сами

погибнут, либо их истребят коренные народы… |

The founder of Molokanism was

the

vagrant rural tailor from Tambov province S. [Simeon] Uklein, who

proclaimed

that the ideal original Christianity is that which has been not

deformed by

the churches. His followers refused to worship icons and everything

that is man-made, including idols. It is only possible to worship the

Living God. They refused the cross as

it is supposedly inappropriate to glorify an instrument of murder. They

began to calculate holidays only by the lunar calendar. And finally,

they completely rejected the church hierarchy, the institute of

clerics,

any Saints and legends, and they only recognize the Bible as the Word

of God.

In response, severe reprisals from the authorities and official church

followed. One of the measures of the struggle against religious

dissidents was to send them to the other side of the Caucasus

[across the ridge]. They thought that "Spiritual

Christians" will either die there, or they will be exterminated

by the native peoples … |

|||

| Вот уже более трех десятков лет

прошло, как я подростком проехал на экскурсионном автобусе от

Орджоникидзе до Еревана. Отчетливо помню: где-то на границе между

Азербайджаном и Арменией автобус вскарабкался на перевал, и нам

открылась крохотная деревушка, каких немало встречается на склонах гор.

Но тут меня будто током ударило: из переулка вышел типичнейший русский

старец с окладистой бородой. Кто-то уважительно сказал

«cтароверы», и в автобусе воцарилась тишина. |

So far more than 30 years have

passed since I, as a teenager, have traveled on a tourist bus from

Ordzhonikidze [now Vladikavkaz]* to Yerevan. I distinctly

remember that somewhere

on the border between Azerbaijan and Armenia the bus crawling up a pass**,

and one of the many tiny villages on the mountain slopes appeared. But

I was shocked [struck by lightning] to see a typical Russian elder with

a broad beard walking in an alley. Someone respectfully said: "Old

Believers",

and the bus became silent. [* Capital of the Republic of North Osetia, Russian Federation. ** See illustrations in "Caucasus Roads".] |

|||

| Иван Миндрин — пресвитер

Орбельяновской духовной общины — очень похож на того старца: крупный,

кряжистый, с окладистой серебристой бородой. И, что самое

поразительное, родом он, да и большинство членов этого собрания молокан

— как раз из тех горных районов между Азербайджаном и Арменией. |

Ivan Mindrin, the presbyter of

the Orbel'ianovka spiritual community, looks very similar to that

elder:

large, husky, with a broad silvery beard. And, most amazing,

he and the majority of the members of this Molokan congregation

came from those same mountain areas between Azerbaijan and Armenia. [See Molokans

in Azerbaidjan, and Molokans / Jumpers in

Armenia.] |

|||

|

||||

| — Наши предки – выходцы из

Саратовской, Ивановской, Новгородской областей, — пересказывает Иван

Павлович устные предания молокан. — Когда их высылали, многие погибли в

дороге. Другие, обессилев, оставались в казачьих станицах и селах на

Ставрополье. Но большинство перевалили через Кавказский хребет и

основали много русских сел, в основном в безлюдной гористой местности.

Духовные христиане общались между собой. Каждый год представители всех

общин собирались в Грузии, в селе Воронцовка, на совет. Рассудительно

решали проблемы, помощь давали нуждающимся. |

Ivan Pavlovich retells Molokan

oral

history: "Our ancestors were natives of

the Saratov, Ivanovo,

Novgorod areas. When they were exiled, many died along the way. Others,

having

grown

weak, stayed in Cossack villages and villages in Stavropol. But

the majority passed through the Caucasian

ridge and founded many Russian villages, mostly in unpopulated

hilly terrain.

Spiritual

Christians communicated among themselves. Every year representatives of

all communities gathered in Georgia, in the village of Vorontsovka*, for

a big meeting. They solved problems judiciously, and gave help to the

needy." [* Now Tashir, Armenia,

at top of map.] |

|||

| Пресвитером Ивана Павловича

избрали члены собрания, те же бабушки и дедушки. После чего их решение

утвердили представители четырех других собраний молокан. На этом и

заканчивается соподчиненность структур

духовных христиан. Кроме своей

паствы, Иван Павлович ни перед кем не отчитывается, ни от кого не

зависит. |

Presbyter Ivan Pavlovich was

selected by the members of the congregation, the same grandmothers and

grandfathers. Then their decision was ratified by representatives of

four other Molokan congregations. That's basically all there is of the

hierarchy of Spiritual Christians. Ivan Pavlovich does not report to,

nor depend on, anybody but his congregation. |

|||

| — Даже если к нам на собрание

придет другой, гораздо более знающий пресвитер, он здесь будет только

как гость. Никакого права вмешиваться в жизнь общины он не имеет. |

"Even if a much more

knowledgeable presbyter would come to our prayer meeting, he would only

be a guest. He has no right to interfere with the life of [our]

congregation." |

|||

| Но опасность авторитаризма

собранию молокан не грозит. И дело не только в здравомыслии Ивана

Павловича, который сурово осуждает тех светских и духовных лидеров,

которые и в преклонном возрасте, уже выжив из ума, продолжают цепляться

за свое кресло. Пресвитер, говоря светским языком, работает

исключительно на общественных началах. Никаких льгот, никаких

подношений.

Да и вообще

все службы, все требы —

будь

то крещение

ребенка, освящение дома или бракосочетание — пастыри молокан выполняют

бесплатно. «У нас не покупная вера», — с гордостью говорят

они. |

Authoritarianism

is not a threat or danger to a Molokan congregation. And it's not

because of the clear mind of Ivan

Pavlovicha who severely criticizes those secular and

spiritual leaders who are of an old age, already lost their mind, and

continue to cling to their throne. Simply speaking, the presbyter works

exclusively on a volunteer basis. He doesn't receive

any privileges or gifts. Molokan presbyters [pastors] perform all

services free-of-charge, whether its christening a child, sanctifying a

house, or [performing] a wedding. They proudly say: "We don't buy our

faith." |

|||

| Каждое воскресенье

орбельяновские молокане собираются в церкви, которую девять лет назад

построили своими руками, по собственным чертежам и исключительно на

собственные деньги. Поют духовные песни — старинные, хранимые

«спокон веков».

В самом полном сборнике их 1116. Поют

самозабвенно и очень красиво. Молятся на коленях, истово. Искренность

молитвы — единственный критерий: «Господа Бога хоть в сарае

почитай, лишь бы от чистого сердца». Затем читают те псалмы, к

которым в этот день у братьев и сестер душа лежит. В праздники у них

«хлеб» радости, на похоронах — «хлеб» печали.

Это одновременно и жертвоприношение, и скромное угощение без спиртного.

|

Every Sunday the Orbel'ianovka

Molokans gather in a church which they constructed nine years ago

with their own hands, using their own blueprints, and only their own

money. They sing

ancient spiritual songs preserved "from time immemorial". There are a

total of 1116 songs in their collection [songbook]. They sing

selflessly and very

beautifully.

They devoutly pray on their knees. Sincere prayers are the only

requirement: "One can praise the Lord in a shed, but only if it's

sincere [from the bottom of your heart]". Then they read those psalms

desired by the brothers

and sisters on that day. During holidays they have a "bread [meal]"

of joy, and during a funeral a "bread [meal]" of grief. This [meal]

simultaneously is both a sacrifice and a small treat without alcoholic

drinks. |

|||

| Но не только стойкостью в своей

вере известны русские иконоборцы. Куда бы ни забросил их злой рок — в

Кавказские горы, в Таврические степи, в глухие леса Канады— везде

духовные христиане прославились своим исключительным трудолюбием. |

But Russian ikonobors* are known not only for their

strong faith. It doesn't matter where their

malicious fate would send them, to the Caucasian mountains, to the

Taurian steppes**, to the

dense forests of Canada*** —

everywhere Spiritual Christians have become

famous for their hard work. [* In 1734, the Russians issued a decree against Ikonobors, dissidents who refused to believe in idols, a heresy. ** Tavria is now the South Ukraine area of the Crimea and Zaparozhie provinces. See: 1882 map, and 1891 Map of the Black Sea Area. Molokans live east of the Molochna river, often called the "Milky Waters" region. See map of Molochnaya Doukhobor and Molokan Settlements, and map of Molokans today in Melitopol region, Zaparozhie province, Ukraine. *** Doukhobors were offered land in the praries of Saskatchewan, central Canada. See photos in: The Doukhobors in 1904 and The Hyas Doukhobor Settlement] |

|||

| — Школа только зимой, —

вспоминает свое детство в горах Азербайджана Ольга Богданова. — А чуть

потеплеет — грабли, вилы на плечо и на работу. Подростки вдвоем одного

быка запрягали, вдвоем одну борону ставили. Скидывали в телегу камни,

освобождали клочки земли под картошку. Все работали с утра до ночи. |

Olga Bogdanova recalls about her

childhood in the mountains

of

Azerbaijan: "We only went to school in the winter. And when it got

a little bit warmer, I had to take a rake and a pitchfork on my a

shoulder and go to work. Two teenagers together could harness one bull

[ox], and together they can pull a harrow. To clean plots of land to

plant potatoes, they loaded rocks on a wagon. Everyone

worked from dawn to dusk." |

|||

| Жизнь у переселенцев из России

была очень тяжелая. Хотя колхозы молокан неизменно становились лучшими,

неизменно «вытягивали» среднерайонные показатели, однако не

то, что премий, а вообще «живых» денег они не видели. И

даже свет в их села проводили в самую последнюю очередь. У молодежи

практически не было возможности продолжить учебу, устроиться на хорошую

работу. А тут еще начиная с 50-60-х годов местные националисты стали

все более и более притеснять русских. И молокане начали возвращаться в

Россию. Тем более что у нас о таких работниках только мечтали. |

Life for Russian immigrants was

very difficult. Even though Molokan collective farms would become the

best, and always "endured" to get good average regional [production]

indices,

they never received incentives and in general they did not see any

"real"

money. And even the electricity in their villages was installed last.

The youth practically did not have an opportunity to continue to study,

or to

get good jobs. More over, beginning in 1950-1960, the local

nationalists started to oppress the Russians more and more. And

Molokans

have begun to return to Russia. In addition, one can only dream about

such hard workers. |

|||

| — С руками-ногами тянули, —

вспоминает И. Миндрин. — Ни прописки, ни справок не требовали — только

работай. Я сюда в 1963 году с женой и тремя малолетними детьми приехал

—

даже с военного учета в Азербайджане не снялся. Все сделали, через

военкомат утрясли — лишь бы на виноградники пошел. Потом руководство

совхоза даже ходоков в

молоканские села посылало — приглашали

перебраться на Ставрополье. |

I. Mindrin recalls: "We were

strongly persuaded [pulled by our hands and legs]. Neither registration

nor any papers were required, just work. I came here in 1963 with my

wife and three

young children. Even my military registration was still in

Azerbaijan. They did everything possible to solve the problem so I

could start to work in the vineyards. Then state farm directors sent

representatives to Molokan villages

[in Azerbaijan] to invite them to Stavropol' province." |

|||

| Любопытная деталь: именно

молокане полвека назад доказали жителям Орбельяновки и близлежащих сел,

что на здешних землях можно выращивать картошку. И до сих пор они

слывут лучшими картофелеводами в

округе. |

An interesting fact: Molokans

50 years ago proved to the residents of Orbel'ianovka and nearby

villages that it is possible to grow potatoes on the local land.

And till now they have a reputation for being the best potato growers in

the district. |

|||

| Еще чем отличались староверы,

так это строгостью нравов. Ругнуться при

старшем — ни-ни. Появиться на

людях в короткой юбке, без платка или в расстегнутой рубахе — срам.

Жили в одном доме: старики, родители, дети, внуки. Ели из одной

огромной миски, вместе шли на работу. Алкоголь, табак веками были под

запретом. И даже в послевоенное время выпивали только осенью, когда

азербайджанцы привозили из долины вино и меняли на картошку. Ныне же

все изменилось. |

One more thing that

distinguishes Old Believers*

is their conservatism. Swearing in the presence of elders is a

no-no. To

appear in public in a short skirt, without a scarf, or in the

unbuttoned

shirt is a shame. Everybody lived in one house: elders, parents,

children,

grandsons. Everybody ate from one huge bowl, and went to work together.

Alcohol and tobacco were prohibited for centuries. And even during

post-war times, they drank only in the autumn when Azerbaijanis brought

wine

from the valley and exchanged it for potatoes. Nowadays all has

changed. [* The author confuses Molokans, an old faith, with Orthodox Old Ritualists, Old Believers.] |

|||

| — Наши дети ушли из рук наших,

из повиновения и послушания, — сокрушается пресвитер. — Вспоминать аж

жутко. |

The presbyter grieved: "We have

no control over our children, they don't obey us or listen to us. It's

terrible to recollect." |

|||

| — Сейчас вся молодежь в блуд

подалась, в бесчинства, — вторит ему Марфа Богданова. — Весь мир под

одну музыку танцует. Вот и наши дети пропали. |

Marfa Bogdanova echoes: "Now all

youth have sex and affairs, in excesses. The whole world dances

to the same music. So our children got lost." |

|||

| Да, это самая большая боль

молокан. Их дети и внуки отходят от веры — самой чистой, но и самой

тяжелой в служении. Мирские прелести и соблазны предпочитают заветам

предков. Хотя, с другой стороны, и винить их трудно: если не будешь

жить, как все — заклюют. Времена самопожертвования во имя Слова

Господня, видимо, прошли. |

Yes, it is the biggest Molokan

pain. Their children and grand-children are leaving the faith,

the most pure

but also the most difficult to obey. They prefer the worldly

attractions and temptations to the teachings of their ancestors.

Though, on the other hand,

it's difficult to

blame them, because if you don't live like everybody else, they'll pick

on you.

The times for self-sacrifice in the name of the Word of the Lord,

probably has

passed. |

|||

| Но пока они, старики, еще живы –

жива и вера малоканская. И торжественное песнопение вновь наполняет

храм в Орбельяновке: |

But while the elders are

still alive, the Molokan faith is alive. And solemn church singing

[chanting] again fills a church in Orbel'ianovka: |

|||

| «О,

отвори, отвори, Господу двери свои. Он в твое сердце войдет, Мир и любовь принесет!». |

"About,

open, open, To the Lord the doors. It will enter your heart, Peace and love will bring!". |

|||

Back to Molokans Around the World